Contesting the City (Liddy)

Justyna Wubs-MrozewiczLast week, several history-students at the @UvA_Humanities valiantly faced their oral B.A. literature exams. Among the books discussed was also one of our #RetroConflictsInspirations: Christian D. Liddy’s ‘Contesting the City’. In vivid discussions, many students summarized the main argument of the book along the following lines: English citizenship was an inherently contested concept.

If citizens were equal by oath and constitution how could some of them legitimize their rule over the rest? Tracking the voices and actions of citizens, councils, and mayors in the public sphere – in space, time, and communication – Liddy shows that we should not consider conflict as a mere disturbance to a generally accepted top-down oligarchic rule. Instead, conflicts were common to the anything but static urban political thought and practice. Here we can tie his thoughts to our research: did Hanseatic burghers and merchants consider conflicts in and around their cities unanimously as disturbances to economic, political, and social order? Or should we maybe allow medieval burghers and merchants more differentiated views of their world? [....]

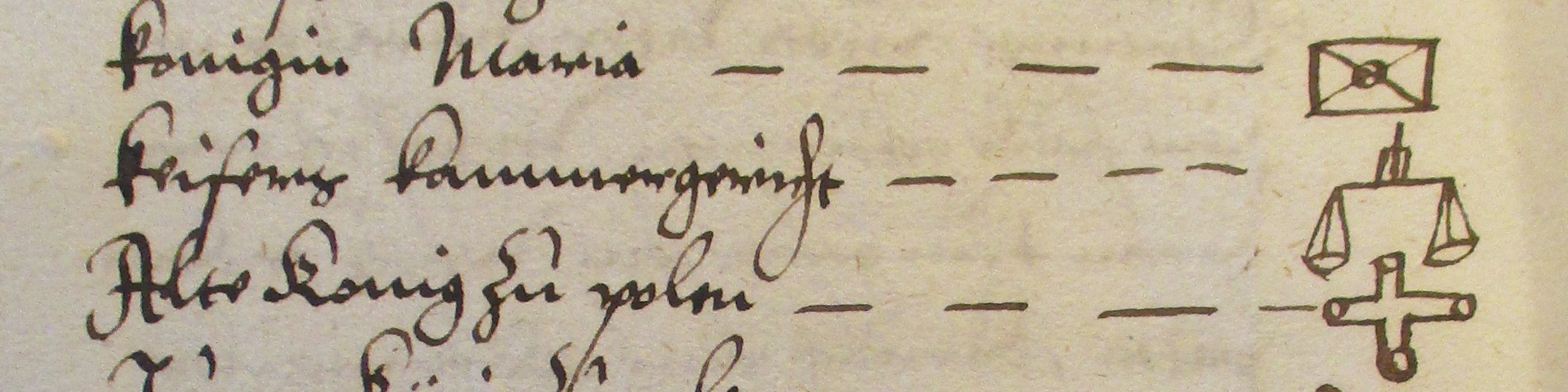

In today’s #RetroConflictsInspirations, we take a look at ‘The Material Letter in early modern England’ (2012) by @JamesDaybell. He draws attention to interesting choices in letter writing: tools, conventions, ways of posting letters, keeping them (partially) secret or copying them. These were certainly not random, but instead all constituted a thoughtful part of the communication. The focus in the book is primarily on letters in diplomatic (elite) exchange or in connection to military operations in England, but the observations are just as applicable to mercantile letters and correspondence between city councils. For instance, we can add that cryptography occurred also in the Hanse area. Around 1558, a Hanseatic father provided his son with a code where the English Queen Mary, the Reichskammergericht and the Polish King were referred to in symbols. While not as common yet as in diplomatic exchanges and in later times, such peeks from sources show that Hansards were aware of the epistolary possibilities.

In today’s #RetroConflictsInspirations, we take a look at ‘The Material Letter in early modern England’ (2012) by @JamesDaybell. He draws attention to interesting choices in letter writing: tools, conventions, ways of posting letters, keeping them (partially) secret or copying them. These were certainly not random, but instead all constituted a thoughtful part of the communication. The focus in the book is primarily on letters in diplomatic (elite) exchange or in connection to military operations in England, but the observations are just as applicable to mercantile letters and correspondence between city councils. For instance, we can add that cryptography occurred also in the Hanse area. Around 1558, a Hanseatic father provided his son with a code where the English Queen Mary, the Reichskammergericht and the Polish King were referred to in symbols. While not as common yet as in diplomatic exchanges and in later times, such peeks from sources show that Hansards were aware of the epistolary possibilities.