Stuart Carroll: ‘Memorials and Conflict Resolution in Early Modern Europe.’

Justyna Wubs-Mrozewicz

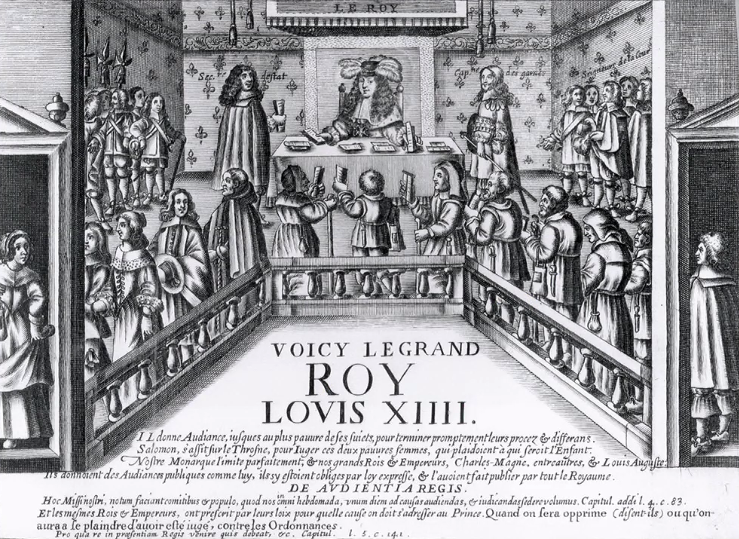

Stuart Carroll introduced himself to our audience as a living contradiction: a historian of violence, but not much interested in war. It’s a puzzle appropriate to Carroll’s research on early modern France. Louis XIV, for example, was no stranger to violent conflict, he led France into many wars and financing them was a defining issue of his reign. But violence amongst his subjects was another issue. Like many early modern monarchs, Louis was drawn to the idea of Solomonic kingship. He was keen to be shown arbitrating his subjects’ disputes, as in the picture above, and this peacemaking was more than propaganda in many cases, says Carroll.

Most violent crimes, including many murders, in early modern Europe ended in arbitration. At the heart of this mode of peacemaking were acts of ‘expiation’. Some expiatory acts, like pilgrimage, faded away in the early modern period, but others, like fines, are still with us. Carroll’s presentation focuses on cross building as a form of expiation. This practice can be seen in both Catholic and Protestant regions, although the evidence can be patchy as crosses have been lost to hazards both natural and man-made. Few expiatory crosses remain in France because of destruction during the Wars of Religion and French Revolution, but many survive in central Europe, such as the 7000 Sühnkreuze in Germany.

These crosses offer a fascinating view of the ways in which early modern actors brought together various and seemingly contradictory ideas to shape conflicts. The crosses are firstly and most obviously Christian monuments. But that characterization is complicated by the fact the they were produced on the instruction of secular peacemaking authorities. By understanding the crosses as part of a formal judicial procedure, Carroll explains, we get a clearer sense of the way in which religious and secular forms of conflict management were integrated in the early modern period.

Another important aspect of the crosses is their role in society after their construction. While their stated purpose was to communicate penance and the end to a particular conflict, their forms often suggested otherwise. Carvings of weapons on the crosses served to commemorate, and in some measure to celebrate, deaths in duels. This iconography gave rise to ghost tales and local superstitions, which reveal how the crosses’ meaning in the popular imagination was more ambiguous than the official, straightforwardly peaceful, account would suggest.

In these monuments to reconciliation, we learn much about conflict in early modern Europe – where peacemaking coexisted with the memorialization of a glorious death , and where secular and religious iconography were intertwined.

Stuart Carroll is Professor of Early Modern History at the University of York, and has written widely on premodern violence.

Stuart Carroll: contact details and research. See e.g.Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe (2009) and 'Thinking with violence', History and Theory 56/4 (2017).

Comments

Add Comment